Alone, Together: You, Me, and ChatGPT

In a world disheartened by dating apps, people are increasingly turning to silicon-based sweethearts.

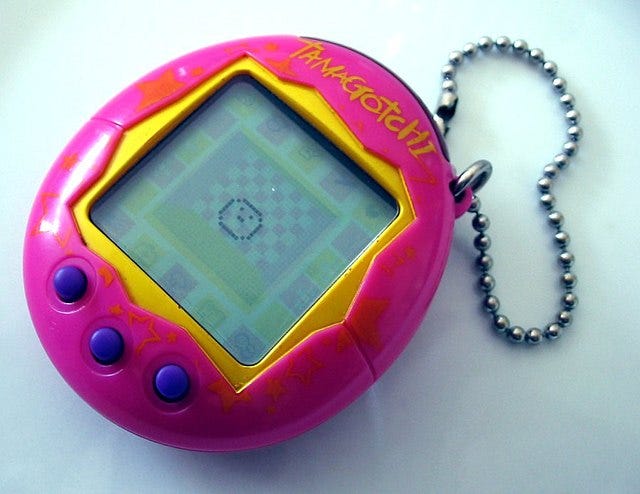

My friend, McQuaid, and I carpool to the climbing gym twice a week (read as: he picks me up and I yap ). Inspired by the newest season of The Ultimatum, our reunion debrief turned into an in-depth discussion about the declining quality of dating apps. We concluded that we both hated them. When he asked me my reasoning, I answered: It feels like I’m going in to feed my Tamagotchi. These aren’t real people to me.

For this reason, I’ve always found it a little strange that folks are so able (and willing) to use dating apps. It’s recently dawned on me, however, that the Tamagotchi-like quality of dating apps might be exactly what most people like about them.

Also, this is a Tamagotchi, in case you’re a late Gen Z:

If I urge you to consume one piece of media this year, it’s the February 3rd episode of the Vox podcast, The Gray Area with Sean Illing, called “Do Americans have too much ‘me time?’” (with guest, Derek Thompson, staff writer for The Atlantic).

In this episode, Illing and Thompson discuss how much of the “loneliness epidemic” is real and how much is actually self-constructed solitude. They consider whether or not this crisis is outside of our control or if we’re simply choosing to be alone at a historically unprecedented rate. Most of their discussion stems from Thompson’s (somewhat polarizing) January 8th article, titled “The Anti-Social Century.” So, actually, I lied. I think you need to consume two pieces of media this year.

Over the past 25 years, the average amount of time that Americans spend in face-to-face socialization has declined by about 20%, with some demographics (like young people and unmarried men) seeing a decline close to 40%. Thompson cites two root causes from the 20th century that set up the social decline of the 21st: the first is the car, which allowed us to privatize our daily lives, and the second is the television, which allowed us to privatize our leisure time.

Since the first TV in 1927, the screen has taken on many new forms—as entertainment shifted from flatscreens in the living room to personal phone screens in the palms of our hands, media consumption has become increasingly more individualistic. “TV dinners” over Wednesday night airings of Survivor were, in some ways, still social events; at the very least, they were a way to connect through a shared (if lazy!) experience with your family and friends. Nowadays, Netflix’s reign over cable programming has disintegrated scheduled socializing, paving the way for on-demand access. The on-demand economy, like the Industrial Revolution, has its trade-offs. And any “economic mitzvah” (to quote Thompson) has its costs.

One of these costs is the fact that the on-demand economy is essentially a dopamine-seeking reward system. Getting more dopamine more efficiently necessarily requires spending less face-to-face time around actual people because other people cause friction. It’s altogether easier to order delivery instead of going out to a restaurant, throwing on a comfort show instead of getting dressed up to see friends, and scrolling through animal videos on TikTok instead of volunteering at a shelter. Talking to these [spooky voice] “other people” via text is also just…easier. We can do it from the comfort of our own homes—naked, unshowered, in PJs. You name it.

It’s not just our entertainment economy: any relationship—platonic or romantic—is its own isolated dopamine reward system as well. Therefore, in an age where every facet of our lives redirects us to seek pleasure more efficiently, it should come as no surprise that we are trending towards optimizing our companionships. That means people are pursuing deep, personal relationships with AI chatbots.

It’s weird, but it’s going to get more common. And it’s also going to get weirder. As AI technology improves and becomes multimodal (i.e., more able to hold a verbal conversation, not just to respond to texts), many people will find that “silicon-based friendships and relationships are just richer than carbon-based relationships.” In other words, having relationships with AI agents will be easier (more frictionless and more efficient) than having relationships with human beings.

“Phenomenologically, what is friendship?” Thompson asks us. He notes that for many, friendship is mostly having a “voice, or text-based conversation with an entity that is not [physically] there.” Moreover, we put a necessary amount of love and trust into these non-embodied relationships—in order to text or call about personal issues, we have to trust that our feelings and emotions are being cradled, reciprocated, and responded to appropriately. We have to trust the disembodied agent on the receiving end.

Loving and trusting the concept of the person on the other end of a phone call is not so difficult, especially because we often know this person in their embodied form. Still, we do have to change the form of this trust—we have to believe that they’re not sharing the details of our intimate lives with their roommates on speakerphone, for example.

Romantic relationships also look different in our modern age; the median age of first marriage is over thirty for the first time ever. It’s not hard to posit that among individuals in long-term relationships, most partners are engaging in some sort of text-based, tech-mediated form of communication. More couples these days are long-distance, working full days apart, or physically separated for a host of other reasons. Our phones help us maintain the emotional intimacy required to sustain these relationships.

For single people, there are loads of options in the online era. Popular options include sliding into Instagram DMs, downloading Hinge, or asking your friend to give their friend your phone number. Having an AI partner is not that far off for a self-prescribed, self-isolating population. Especially since this AI partner is a sure-fire, rejection-free way to satisfy some of the biological loneliness cues we’re increasingly apt to ignore.

Other good bits from this episode

AI companions are not the only result of the antisocial economy, but the are the focus of this week’s UI&AI posts. Thompson makes a gajillion valuable points in his article, so here are some highlights, in case robot romance wasn’t your cup of tea:

The disintegration of the “village.” Brown University sociologist Marc J. Dunkelman uses “rings of connection” to refer to our social networks. The innermost ring, or “family,” refers to the closest, most intimate relationships that teach us love. The outermost ring, or the “tribe,” refers to the distant “in-group” that teaches us loyalty or ideology (e.g., being a Philadelphia Eagles fan). The middle ring, or the “village,” is neither here nor there—it’s the neighbours, shopkeepers, or community members who may not share our values and beliefs, but whom we nevertheless engage with because of our local membership. The village teaches us tolerance, and the village is the one that suffers most from online social networking.

Focal politics. Political winners in the anti-social century operate at the “all tribe, no village” level. Political issues have shifted from having a local focus (e.g., improving one’s own community through the democratic process) to having a focal focus (e.g., “what national media gets us to focus on, whether or not it’s relevant to our local interests”).

The need for chaos. The antisocial turn—especially among men—leads to chaos politics. Danish political scientist, Michael Bang Peterson, refers to “the need for chaos” in reference to specific demographics that respond favourably to conspiracy theories and are prone to act in opposition to institutions. One of the strongest correlates to the need for chaos is self-isolation. These isolationists aren’t seeking friendships like we expect from lonely people. They’re seeking power and validation, which they often do by joining an online antiestablishment group, rather than by making real-life friends.

Trenches Preview

We dive into the promises and perils of AI companions and what it actually means to “date” ChatGPT.