Is human comfort more important than human experience?

Using AI to optimize our lives at the risk of missing out on real, tangible *human stuff.*

First, I’d like to thank those who read “About Death.” Moving forward, I’ll post Trenches on Monday, following Sunday’s Tower post to offer some concrete applications, readings, and real-world examples of my conceptual Sunday musings. “About Death” was a bit of a stand-alone teaser trailer, if you will—in other words, don’t fret! Plenty more death where that came from! This week is about the emotional human experience and our preventative prioritization of comfort. It’s also about architecture (tomorrow).

Insofar as they are any good, all happiness podcasts, self-help books, and mindfulness exercises have one thing in common: emphasizing that all emotions have their rightful place in the human experience. Although we tend to prioritize “happiness” or joy above all else, other feelings (like anger, sadness, anxiety, guilt, etc.) all harbour meaning in our self-concept and value in the greater scheme of being human. More on joy at a later date (trust me).

Basically, no matter how you shake it, you have to feel stuff. Even the bad stuff. We know this (in theory), but do we really consider what this means from the perspective of our physical discomfort? I don’t think so. We may recognize the physical loci of many feelings—desire is in the chest, anxiety in the stomach, anger in the head, whatever—and we (sort of) know how to quell those physical sensations and, thus, their associated emotional burden. Countless tactics—like breathing exercises, meditation, yoga, drinking peppermint tea, and eating keto—exist to change our external environment, thereby improving our internal state. But in many cases, our desire to maximize physical comfort takes over before any emotions—negative, or otherwise—have had the chance to arise. Changing our environment becomes a preventative measure, rather than an adaptable response.

Sometimes, this is a good thing. If there’s a 90% chance of rain, you are justified in carrying an umbrella to avoid getting wet. If you have a huge presentation tomorrow and you always have trouble sleeping the night before public speaking, you are justified in cutting down your caffeine intake for the day. Preventative adaptation is an inherent part of getting better at being alive.

Sometimes, this is a bad thing. Humans are not meant to live in climate-controlled, programmable eco-chambers. Would we be free from any unexpected harm? Yes, but we’d also miss out on any unexpected pleasure.

Humour me and reflect upon one of your “core memories” (to borrow a term from the movie Inside Out). Before any details take shape, you may recall the memory’s sensory elements. “When Jess and I got caught in a torrential downpour and had to run home soaking wet,” or, “When I was so nervous for my first conference, I had to hide behind the podium because my right leg felt like it was full of fireworks!” Both of these memories involve an inherent, physical discomfort that has somehow spun itself through the inner machinations of my mind to create a lasting positive impression. Blah blah. So what?

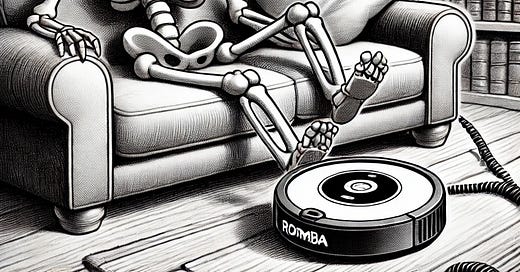

Artificial intelligence has given us new, potent avenues for preventative adaptation and maintaining homeostatic comfort. Need to send a rejection email to a prospective employee? Ask ChatGPT instead of strenuously crafting a response and feeling bad about it! Love having a clean house but hate vacuuming? Set a cleaning schedule for your Roomba! Feel bad for Roomba Maid™? Set your schedule at a time when you’re not home! Now you don’t even need to think about Roomba Maid™! We are trending toward the deadening of any sensation via a preventative and technologically adept manipulation of our environment. To avoid unpleasant feelings—feelings like remorse, disgust, and guilt—we simply avoid letting them surface instead of responding to them when they do.

AI can help us numb our physical and emotional states in many ways, most of which are proactive. In fact, much of what AI does for humankind is a sort of preliminary optimization calculus. Making one’s life “easier” or “more comfortable” is the end goal of many consumer-facing technologies. In and of itself, this isn’t a problem. But the question is: How much do we as a society actually value difficult, uncomfortable experiences? Do we need to feel the bad stuff to make the good stuff meaningful? If we don’t feel the bad stuff, can we even feel the good stuff at all (given that “bad” and “good” exist in tension with, and reference to, one another)?

Maybe it’s a matter of opinion. I don’t necessarily believe that suffering builds character, but I think there is a value—a sparkly, magical je ne sais quoi—in living through the whole spectrum of human experience. Mark your calendars…this could be the only time I will ever argue for a reactive approach over a proactive one.

Trenches Preview

Auto-modulating temperature based on how many human beings are in a building at any given time is an application of AI-mediated preventative adaptation in architecture.

"Living through the entire spectrum of human experience" reminded me of a NYT Daily podcast episode that discussed the reliance of air conditioning in the US and maybe sometimes, instead of always being in an artificially cooled environment, we should just feel a little uncomfortably hot and sweaty in the summers instead. Thanks for writing this post!